Tree Structured Data (Web Documents)

Web documents

There’s a lot of useful data out there on the web. For example, this disambiguation page on Wikipedia for “Python”, or this list of courses offered by the CSCI department.

Is there any data out there on the web that you’d like to be able to analyze, do computation over, or otherwise make use of? Then you’re in luck: today we’re going to start a portion of the class devoted to working with the kind of data you’ll find on a webpage.

You’re probably viewing these notes in your web browser. Most browsers have a “View Source” menu item somewhere:

- In Safari: Command + Option + U;

- In (Windows) Firefox: Control + U;

- In (MacOS) Firefox: Command + U.

Use this option to open up the source of this page. What does the source look like? There’s a lot here, so instead let’s start with a simpler page: this one. (You can also find this on the CS department’s page here). Its source looks like this:

<html>

<head>

<title>This is a page</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Here is a paragraph of text</p>

<p>Another paragraph, with <strong>bold</strong> text</p>

<p>And a list:

<ul>

<li>Item 1</li>

<li>Item 2</li>

</ul>

</p>

<p>And a bolded list:

<strong>

<ul>

<li>Item 1</li>

<li>Item 2</li>

</ul>

</strong>

</p>

</body>

</html>

What do we notice about the structure of this source?

Webpages are generally written using this language, which is called HTML (short for Hyper-Text Markup Language). HTML is made up of tags (the things in angle brackets). A tag can contain text; it can also contain other tags, which can contain still more tags, and so on.

Why does HTML look like this? Because HTML documents have structure. They aren’t just plain text: they have a header and a document body, formatting like paragraph and boldface text, and even formatted lists.

We won’t really learn how to write HTML in this course. We will however, learn how to do computations over HTML documents in Python, because web pages can be an excellent source of data. If we want to extract that data and work with it, we need to be able to turn it into a useful form.

So: how might we represent the HTML document above in a data structure?

- We could hold the HTML document in a string, but a string doesn’t have any structure to it. It would be tough to do useful computation on just a string. For instance, we might want to look at the above document and extract all the entries in the second list. A string wouldn’t help us with that at all.

- We could turn the document into a list of words, like we did with Frankenstein and The Death of Arthur. That gives us a little bit of structure (the document separated into words and the bracketed beginning and ending tags) but it’s also not ideal.

The problem is that the tags are nested: tags contain tags which contain tags, and so on. So far we haven’t learned any data structures in Python that are good for working with that sort of document.

Trees

Data with nested structure is quite common in computer science. In CSCI 0111, we saw one example: ancestry trees, recording the parents of individuals (and their parents, and their parents, and so on). Because this sort of data can resemble a family tree, we’ll call it tree structured. Let’s build a tree-shaped data structure for storing HTML documents.

Our tree type will look like this:

@dataclass

class HTMLTree:

tag: str

children: list

text: str = ""

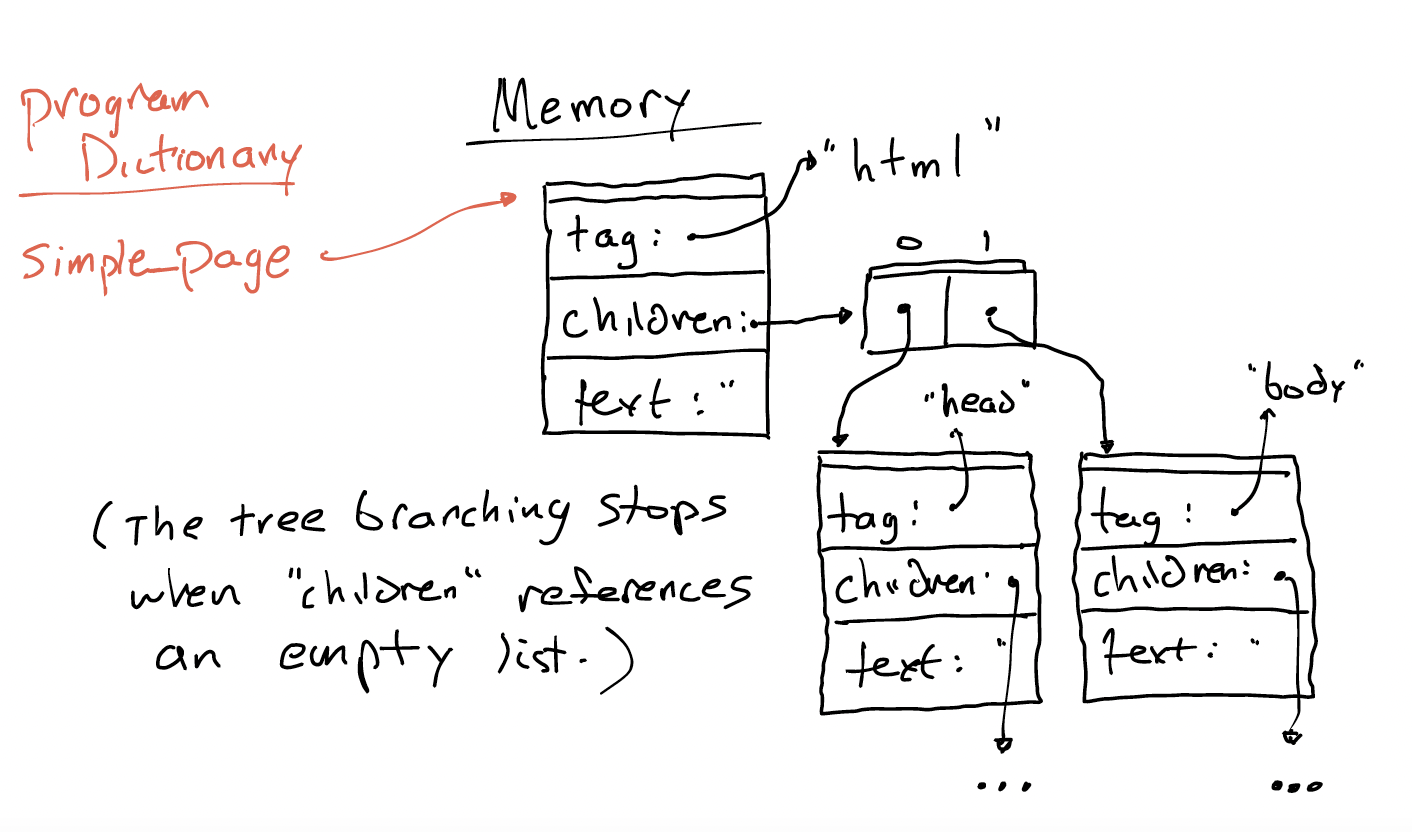

Each instance of the HTMLTree datatype represents a single tag. The name of the tag ('p', 'strong', etc.) is in the tag field. The tag’s children are in the children field.

In the HTML document above, there’s text contained within the tags in some places. In our HTMLTree class, we’ll represent these, not as values in the text field for arbitrary tags, but as objects with tag field equal to 'text'. The actual text then goes in the text field. Objects with a tag value of 'text' should never have children, if we’ve built them properly.

If we wanted to represent the HTML linked above using this data structure, it might look something like this in memory:

Working with HTML

Here’s how we’d create a very basic document in Python:

HTMLTree("p", [HTMLTree("text", [], "Text in a paragraph")])

This corresponds to the HTML:

<p>Text in a paragraph</p>

If our documents get much bigger, defining them by hand in Python like this is going to get pretty annoying. To help with this, we’ve written a little HTML library for the class (which is also where HTMLTree is defined). You can download the

Python file from this link. There’s a function in the library to take a string of HTML and turn it into a tree. Here’s how you might use it to produce HTMLTrees from strings, alongside the purely-Python constructor approach:

from htmltree import *

# directly via constructor

tree1 = HTMLTree("p", [HTMLTree("text", [], "Text in a paragraph")])

print(tree1)

# parsed into an HTMLTree via our helper code

tree2 = parse('<p>Some other text</p>')

print(tree2)

We can also print out the HTML string a tree corresponds to by using the provided print_html function:

> print_html(tree)

<p>Text in a paragraph</p>

This is enough to start working with the HTML source of webpages. Over the next few days, we’ll build the skills needed to search, generate statistics over, and even edit HTML documents. And these skills aren’t just about HTML. Tree-shaped data is common. In fact, you’ve been working with tree-shaped data all semester without thinking much about it.

Exercise: What other tree-structured data formats have you used a lot already? Think about examples from other things you’ve studied at and before Brown.

Think, then click!

Elm trees, oak trees, …

Ok, no, seriously: here are three tree-shaped formats you may be familiar with:

- taxonomies, org-charts, biological parentage, etc.;

- algebraic expressions;

- Python (and Pyret, and Java, and…) code; and

- the English language.

Expressions you might enter into your calculator are all tree-shaped. Consider something like (1+2)*(17/4). The operators are intermediate nodes in the tree, and the numbers are the leaf nodes at the bottom. The same goes for more complicated algebraic expressions. Indeed, the order of operator precedence we all learned in algebra class exists to help us draw the proper tree for an expression: turning something ambiguous like 1 + 2 * 3 into an unambiguous tree, where the order of operations is explicit.

Every time you run a Python program, the python3 executable first turns your program text into something called an abstract syntax tree, which it then tries to optimize and run. You can look at any of the programs you’ve written, and see if you can break it up into a tree: functions and classes at the top level, etc. In fact, Python’s indentation reinforces the idea of the syntax tree.

If you’ve ever diagrammed a sentence in English class, you’ve done manual computation over tree-shaped data. This word is a noun; that word is a verb. And so on.

A Note on Python vs. Pyret lists

This isn’t strictly about trees, but it will come up in a lab soon.

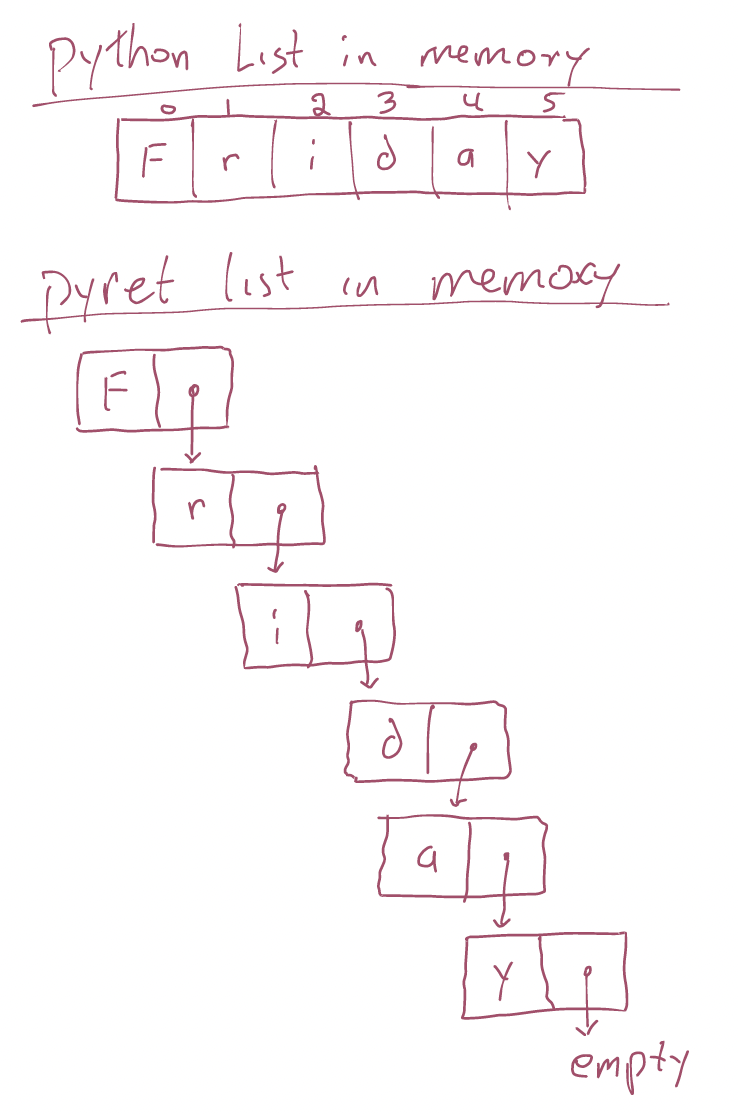

Earlier this week, we used the fact that Python’s lists are contiguous blocks of memory to build very fast set and dictionary data structures. If you took 0111, you might recall that Pyret’s lists don’t work that way. Instead, they are built up recursively—very like the way we built the HTMLTree dataclass. Here’s a sketch of the difference:

You haven’t yet been able to exercise all the skills you developed in 0111 to work with Pyret lists. But those skills are about to become valuable, because, computationally speaking, trees look an awful lot like Pyret lists: they’re a linked data structure, rather than made from one block of memory; the difference is that instead of having a single successor (as in a Pyret list) here a node has multiple successors. <!–

What does that mean?

Exercise: how would I write a function that measures the depth of an HTML Tree? (Hint: start with how you’d measure the size of a Pyret list, and adapt that idea to work for trees.) –>